Share this post!

A human can survive roughly three weeks without food. Without water, three days. But in the absence of air, humans perish in about three minutes. That is the importance of the essential nutrient you should know: oxygen.

Breathing is a vital function that delivers oxygen to all tissues of the body, so that they may utilize food to derive energy. This amazing mechanism is involuntary, yet able to be voluntarily controlled.

This article highlights the role of oxygen in metabolism, nutrients that support oxygen management, how breathing impacts the autonomic nervous system (and stress), the importance of the physiological sigh, and an invitation to raise awareness of your breath.

What is oxygen?

Oxygen is the 8th element of the periodic table. It typically exists in nature as a diatomic gas, meaning that it exists as two atoms of oxygen bonded to each other in the gas state. It is very reactive and a strong oxidizer, meaning it readily takes electrons from other elements and compounds.

Oxygen is the second most electronegative element (after fluorine). Electronegativity is the measure of an atom’s ability to attract electrons to itself, a property that explains oxygen’s usefulness in human metabolism.

Metabolism: Where does oxygen fit in?

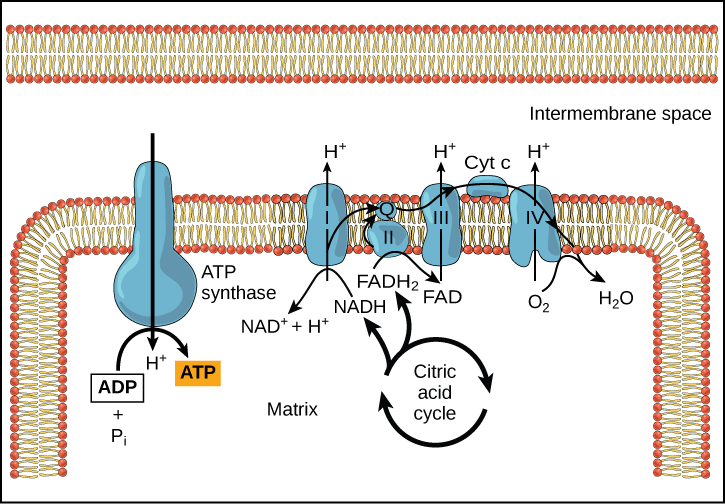

Metabolism is a complex system of chemical reactions that includes the transformation of foods we eat into energy to sustain daily activities in a process called cellular respiration. In the final step of cellular respiration, electrons are shuffled across a series of enzyme complexes called the electron transport chain. This movement of electrons generates the type of energy that our body uses, ATP, by powering the addition of a phosphate group to ADP.

So what about oxygen? It is the final link of the electron transport chain, accepting the electrons as this electronegative atom loves to do. The electron-heavy oxygen combines with positively charged hydrogen ions in the area and forms metabolic water. If oxygen is not there to catch the electrons, cellular respiration stops and eventually the cell dies.

How Oxygen Moves about the Body

Since oxygen readily takes electrons from pretty much anything it can find, this presents dangerous consequences if all of our cells and tissues were to be exposed to free oxygen roaming through the body. That is why oxygen is bonded with a protein transporter called hemoglobin.

Hemoglobin is a protein that consists of four subunits, each with an iron atom that binds strongly with oxygen to safely transport it via red blood cells from the lungs to all other tissues of the body. Deficiency of hemoglobin, or red blood cell count in general, results in the condition known as anemia, which produces symptoms of fatigue as a result of poor oxygen delivery to the mitochondria of bodily cells.

Nutritional Support for Healthy Production of Red Blood Cells and Hemoglobin Includes:

- Iron – required for synthesis of heme

- B vitamins including B6, B9, and B12 – essential for hemoglobin synthesis

- Copper – enzymes containing copper transform iron into its usable form

- Vitamin A – helps cells differentiate from stem cells into their more specialized functions, including blood cells

Exercise is another factor that increases the production of red blood cells, as increased oxygen needs encourage the formation of new red blood cells. Oxygen requirements vary depending on bodily states, including stress, physical activity, temperature, and the state of the autonomic nervous system. Let’s explore ways in which the breath can affect physiological and emotional states in the body.

How the Stress Response Affects Breathing

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is a division of the nervous system that regulates physiological functions such as heart rate, respiration rate, blood pressure, and digestion. It is divided in two branches:

- Sympathetic nervous system, also known as the “fight or flight” or stress response

- Parasympathetic nervous system, also known as the “rest and digest” or relaxation response

As the body perceives stress, the sympathetic nervous system activates and your body subconsciously produces chemicals that increase heart rate and blood sugar concentration to increase available energy. Producing more energy also requires more oxygen, so breathing rate increases as well.

So, more breaths means more oxygen input, and that’s a good thing, right? Not necessarily. More frequent breathing may increase air flow and heart rate, but it doesn’t improve autonomic reactivity to stress, cardiovascular function, or oxygen usage. Let’s explore the benefits of slow, deep breathing.

Effects of Slow Breathing on the Autonomic Nervous System

Although we are not able to control heart rate or hormonal secretions directly, the ability to voluntarily control our breath gives us the opportunity to affect the autonomic nervous system. To ascertain the level of dominance the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems have over cardiac function, scientists use two measurements:

- Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) refers to the coordination of respiration and heart rate, i.e. emphasis on the inhale increases heart rate and emphasis on the exhale decreases it.

- Heart rate variability (HRV) is the measure of variation of time between heart beats

Low RSA/HRV indicates sympathetic nerve dominance over heart rate and respiration, an indication of chronic stress response in the body, while high RSA/HRV indicates parasympathetic dominance and is often associated with cardiovascular fitness, resilience, and better adaptation to stress.

Slow breathing, defined as 4-10 breaths per minute (with average breathing typically at 10-20 breaths per minute), increases RSA/HRV such that blood flow, heart rate, lung ventilation, and gas exchange are optimized. According to many studies cited in the review, six breaths per minute correlates with the most beneficial impacts.

Breathing slowly and deeply shifts the ANS toward parasympathetic control, which should be dominant in resting states. Ideally, the sympathetic nervous system should be under control only during physical exercise and times of acute stressful events, though it is chronically activated in many people.

In addition to the benefits of synchronizing respiration with heart rate, slow breathing also improves oxygen efficiency by reducing “dead space” in the lungs.

Alveolar Dead Space and the Importance of Sighing

Alveoli are tiny sacs in the lungs where oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged during respiration. “Dead space” refers to a volume of air that is wasted by not participating in gas exchange. Normal breathing collapses the alveoli resulting in loss of functional space for oxygen to enter the blood and carbon dioxide to exit. Fortunately, alveoli function is restored by a normal physiological function called the sigh.

Sighs are often considered a type of emotional expression, such as the sigh of relief. A physiological sigh, however, is one that is generated imperceptibly every few minutes (about 12 per hour). The difference between a sigh and a normal breath is the two-phase inhalation, in which a normal inspiration is followed by a second, larger inspiration after a brief pause. This type of sigh re-expands the alveoli, restoring normal lung function. These sighs are so important that they are included in ventilator programs.

The impetus for a sigh is generated in a region of the brainstem called the pre-Bötzinger complex, which is a cluster of neurons that controls normal respiratory rhythm. Mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors, which detect changes in lung volume and pressure and concentration of gases in blood, respectively, determine when it is time to sigh. These receptors receive information from the vagus nerve, a main component of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is hopefully controlling respiration most of the time.

Breathing Techniques

What is the proper way to breathe?

Timing your breath to about six per minute is a great place to start. Many people have success with counting to 5-6 on the inhale, then counting to 5-6 on the exhale.

Need to calm down? Try the 4-7-8 technique, where you inhale on a count of 4, hold the breath for a count of 7, and then exhale for a count of 8. You can also consciously implement a physiological sigh with a two-part inhale, slight pause, and a long, slow exhale.

Slowing your breath may naturally encourage deeper, diaphragmatic breathing. The diaphragm is a respiratory organ made of skeletal muscle that is voluntarily controlled. The movement of the diaphragm dictates how much volume each breath will produce. As you inhale, the diaphragm moves down, giving more space for the lungs to fill and the ribcage to expand laterally. As you exhale, the diaphragm moves back up to push the air out. The greater the diaphragm movement between inhalation and exhalation, the greater the volume of breath.

Finally, breathe through your nose whenever possible. This prominent facial feature warms, moistens, pressurizes, and filters air as it enters your lungs. In addition, nasal breathing stimulates the production of nitric oxide (NO), a vasodilator that enters the lungs and increases the surface area of alveoli and improves oxygen assimilation.

Want to explore the breath with movement? My favorite YouTube yoga teacher, Adriene Mischler, is offering a 30-day yoga journey dedicated to the humble breath.

Connect to Your Breath

Breathing is the most essential function to life and vitality. Slow it down, take it in, and enjoy the ride.

About the author:

Karyn Lane is a current student of NTI’s Nutrition Therapist Master Program. She finds her chemistry degree a useful tool in her study of nutrition and loves to treat herself as a laboratory for new recipes and cooking techniques. You can follow her on Instagram @feel.alive.nourishment.

Image:

Image by kathleenport is free for use by Pixabay

Image by CNX OpenStax is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Image by Brett Jordan is free for use by Unsplash

Image by Max van den Oetelaar is free for use by Unsplash

Learn more about our school by attending an informational webinar.

Share this post!