Share this post!

Gelatin is certainly a food your grandmother would recognize. From bone broths to jello molds, gelatin was found in the majority of our ancestors’ diets. Derived from skin, bones, and connective tissue, this ingredient is an important component of nose-to-tail eating. Although (thankfully?) jello salads have fallen out of favor in American culture, the nutritional value of gelatin is a good reason to consider it a staple of a healthy diet.

In this article, we’ll learn about the history, nutrition, and common forms of gelatin along with some savory and sweet recipes to incorporate more gelatin into your daily routine.

History of Gelatin

Historians have found that the earliest record of the culinary use of gelatin – derived from slow, steady simmering of pig’s ears and feet – dates back to the 1400s. Other discoveries of gelling substances across the ages include kanten, discovered from the congealing stews made with red seaweed in Japan in the 1600s, and isinglass, a gelatinous Russian concoction made from the swim bladders of Beluga sturgeons.

Commercial preparations of gelatin began during the Industrial Revolution, facilitating access to this nutrient by removing the time-consuming element of the long-slow preparations from bones. Later in the 1800s, packaged dessert mixes known as Jell-O came on the scene. Presently, gelatin is used as a food additive in numerous processed foods including puddings, gummy candies, and marshmallows. Gelatin is also an important ingredient in the production of Chinese soup dumplings and aspics.

Aspics and Early Haute Cuisine

Aspic is a savory jelly mold made from congealed meat stock containing pieces of meat, seafood, eggs, or vegetables. Antonin Carême, a French chef who used aspics as elaborate centerpieces for Parisian elites in the early 1800s, is often described as the founder of haute cuisine, having established the earliest trends in fine dining. His influence increased demand for commercial productions of gelatin, and aspics and gelatin desserts became popular.

Gelatin was also an inexpensive staple of the American diet during the Great Depression. Besides being a convenient way to work around the lack of refrigeration technology, gelatin was also a way to add protein, use leftovers, and present simple meals with style.

The wonders of Jell-O were marketed to housewives with pamphlets and cookbooks containing recipes for aspics, salads, and desserts, often with hilariously un-appetizing photos. Author James Lileks has made a career of sharing the best “worst” finds in mid-century recipes and food photography. His book, The Gallery of Regrettable Food, is a treasure trove of such photos and recipes complete with witty commentary. His online gallery of the history and advertisements of Jell-O is also worth checking out.

Despite the potentially regrettable image of meats and veggies suspended in gelatin, there are numerous health benefits to this practice and the consumption of gelatin that will be illustrated below.

Nutritional Profile of Gelatin

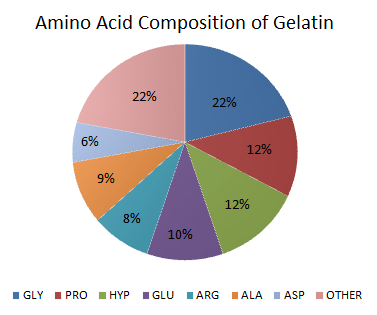

Gelatin is 98-99% protein, with glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline being the predominant amino acids. It is not a complete protein because it lacks tryptophan and is deficient in isoleucine, threonine, and methionine.

Gelatin enhances protein intake by complimenting the amino acid profile found in muscle meats. Muscle meats tend to be high in methionine and low in glycine, therefore consuming meat with gelatin-rich sauces, gravies, or even set in gelatin may deliver amino acids to the bloodstream in a more balanced way.

Glycine is the simplest amino acid, making up about 20-25% of the amino acids in gelatin. It can be synthesized in the body, therefore it is not considered an essential amino acid in the diet. However, evidence shows that the amount synthesized in the body does not support the daily requirements for glycine, which is why it is widely considered to be a semi-essential amino acid.

Functions of glycine in the body include:

- Synthesis of biomolecules, such as porphyrins (including the heme portion of hemoglobin), purine bases (used in DNA), and glutathione (master antioxidant)

- Synthesis of proteins, such as collagen

- Detoxification of benzoic acid, a common byproduct of the body’s breakdown of synthetic chemicals

Together the amino acids proline and hydroxyproline make up about 25% of gelatin content. These amino acids are also deemed nonessential in the diet because humans can synthesize them. However, proline is considered “conditionally essential” in times of illness or stress, and hydroxyproline is synthesized from proline in the body using vitamin C as a cofactor, so it can be considered conditionally essential as well. Dietary needs for proline are among the greatest of all amino acids in the body because of its roles in collagen production, growth, and metabolism.

Other Nutritional Benefits of Gelatin

- Enhances digestive health

- Amino acids stimulate the secretion of gastric juices which aid in digestion. Gelatin also binds water effectively, which helps keep the digestive tract hydrated and soothes the mucosal lining. For these reasons, gelatin is a natural aid in the treatment of inflammatory bowel conditions.

- Protects joints and improves exercise recovery

- Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body. Its synthesis requires adequate glycine, proline, hydroxyproline, and vitamin C. Breakdown of collagen or impairment of collagen production plays a major role in the development of arthritis or joint stiffness. This study suggests that gelatin and vitamin C supplementation may help promote the post-exercise synthesis of collagen.

- Supports healthy skin

- Collagen is also a main structural component of skin. Gelatin intake may improve skin elasticity, reduce the appearance of wrinkles, and protect against damage from the sun and other harmful environmental pollutants.

- Reduces anxiety and promotes restful sleep

- Glycine is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, meaning it decreases the activity of neurons in the brain promoting relaxation and calmness. Research shows that supplementation with glycine may improve sleep quality.

Forms of Gelatin

Bone broth is a great source of gelatin, but powdered supplements of gelatin are also easily accessible. Powdered gelatin can be found in two forms:

- Whole gelatin. This form is used to make gummies and desserts or savory meals set in gelatin. It absorbs water more effectively, and forms a gel in food preparations.

- Hydrolyzed gelatin – also known as hydrolyzed collagen, collagen hydrosylate, gelatin hydrosylate, or collagen peptides. This form of gelatin uses heat to break down collagen protein into smaller peptides or individual amino acids. This form is easily dissolved and absorbed, but it won’t gelatinize.

Gelatin, of course, is not suitable for vegan diets. Amino acids such as glycine and proline can be found in beans, nuts, seeds, and vegetables, such as cabbage, asparagus, and bamboo shoots. Hydroxyproline is almost exclusively found in animal products, so vegans should include foods such as carob chips and alfalfa sprouts as sources of this amino acid, as well as support the conversion from proline by including plenty of vitamin C. Vegan alternatives for gelatin include agar agar and Irish moss.

Gelatin Recipes

The most common use of powdered gelatin is the kid-friendly, jiggly dessert known as Jell-O. This dessert can be prepared from plain gelatin and fruit juice (Knox gelatin or Great Lakes brands have recipes on their packages). Numerous recipes for homemade jello can be found online too, like this one.

For a more out-of-the-ordinary gelatin experience, try this adaptation of a traditional Eastern European aspic dish called Kholodets. Traditionally, this dish requires lengthy preparations of stock made from pig’s feet, knuckles, or other collagen-rich animal parts, but for ease it can be recreated using supplemented gelatin powder. I adapted this recipe from Momsdish.

Ingredients:

- 4 cups stock (I used broth made from my Thanksgiving turkey bones)

- 2 tbsp powdered gelatin

- 1 lb cooked, shredded chicken or turkey

- 1 tbsp salt

- 1 tsp pepper

- 2 tbsp fresh parsley

Instructions:

Dissolve gelatin in 1 cup cold stock to soften, about 5 minutes. Mix with the remaining 3 cups of hot stock to dissolve. Add salt and pepper.

Place shredded meat in a 6-cup Pyrex pan. Cover with parsley and gelatin/stock mixture. Refrigerate until set, about 4-6 hours. Serve with mashed potatoes, vegetables, or salad.

This dish tastes like delicious chicken soup, though much different in temperature and texture than it’s traditionally served. It’s perfect for a lunch on the go. If cold, gelatinized soup sounds too weird for you, try simply adding powdered gelatin to your favorite soup recipe.

Note: it is not recommended to microwave gelatin because of changes to the structure of amino acids, such as proline, that may confer negative health effects.

Adding hydrolyzed collagen powder to coffees, teas, and juices is another easy way to add more gelatin to your diet.

“A Good Broth Can Resurrect the Dead”

Gelatin content is a likely reason for this South American proverb’s claim. Numerous benefits support the use of gelatin as a staple of a healthy diet, though probably not strictly in the form of gummy candies.

About the author: Karyn Lane is a current student of NTI’s Nutrition Therapist Master Program. She finds her chemistry degree a useful tool in her study of nutrition and loves to treat herself as a laboratory for new recipes and cooking techniques. You can follow her on Instagram @feel.alive.nourishment.

Images:; Image by _Alicja_ is free for use by Pixabay; Image by Alexei_other is free for use by Pixabay; Image by Hugahoody is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Learn more about our school by attending an informational webinar!

Share this post!