Share this post!

You may have heard the advice to eat foods of all the colors of the rainbow, but what nutrients are responsible for the pigments and the benefits of brightly colored fruits and vegetables? In this mini-blog series we’ll uncover the phytochemicals that give plants their characteristic colors and highlight a few key nutrients of the rainbow and their benefits.

Why Plants Are Brightly Colored

Before we get into the nutrition of specific colors, let’s think about the ecological reasons for colorful plants. Color primarily serves the purpose of plant reproduction, whether by pollination or spreading its seeds. Hummingbirds, for example, learned that brightly colored flowers indicate a rich nectar source, which is why they are attracted to the color red. For this reason, many flowering plants are brightly colored to attract bugs and birds to pollinate them.

Also, colorful phytonutrients may offer protection for the plant in various ways. An example of this is carotenoids, which offer antioxidant protection from damage by UV or visible light, like sunscreen for plants. Sometimes brightly colored nutrients deter herbivorous animals from eating the plant.

Humans have learned to utilize plant pigments as natural dyes, for their medicinal properties, and of course, to eat them. Eating is a sensory experience and color is the way we associate vision with our food.

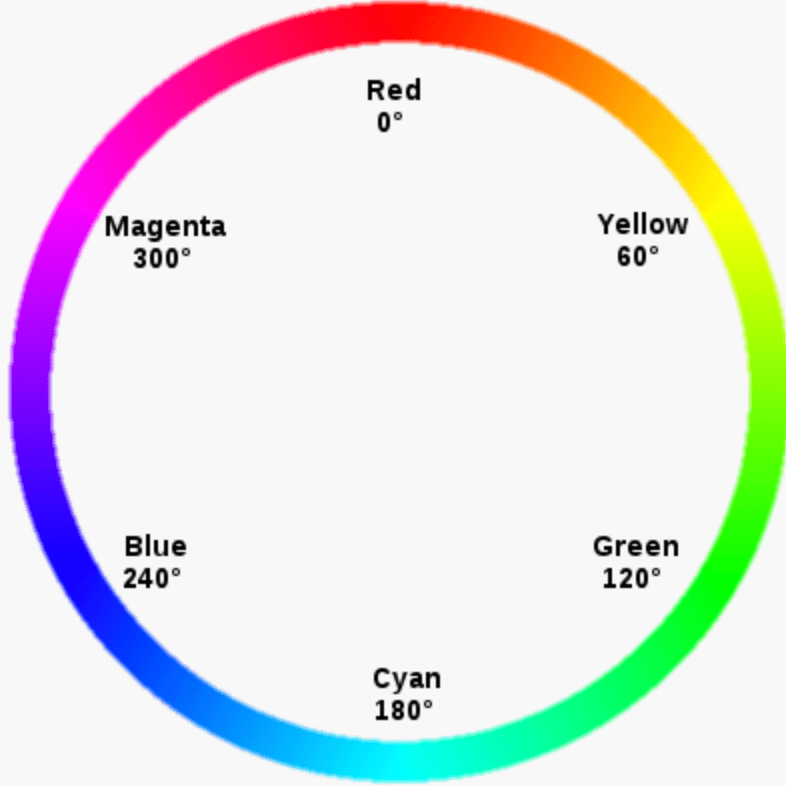

Color Wheels and Hue Angles

Determining colors of specific foods is far from a “black and white” distinction, so to speak. There may be many compounds that offer color in a single plant, such as the yellowish carotenoids in leafy greens that are covered up by the presence of chlorophyll.

Scientists use a system called “CIELAB”, also known as L*a*b*, to qualify small variations in color based on the four basic colors of human perception: red, yellow, green, and blue.

- L* is degree of lightness, where 0 is black and 100 is white

- a* is a scale of redness or greenness

- b* is a scale of yellowness or blueness

Together, these values help determine the hue angle, as represented by the color wheel below.

Colors are associated with the following hue angles:

- Red: <20˚ or >330˚

- Yellow/Orange: 20˚ to 80˚

- Green: 80˚ to 160˚

- Blue: 160˚ to 270˚

- Magenta: 270˚ to 330˚

Hue angles also correlate with antioxidant capacity. Foods with hue angles below 20˚ and greater than 180˚, i.e. in the red, blue, and purple range, typically offer the most antioxidants.

Plant nutrients that are responsible for the colors of the rainbow include:

- Anthocyanins (red, blue, purple)

- Carotenoids (red, orange, yellow)

- Chlorophyll (green)

- Betalains (red, violet, and sometimes orange and yellow)

As you can see, there is a great deal of color variety within these nutrient categories, and we’ll cover them all in the four parts of this blog series: red, orange/yellow, green, and blue/purple. The rest of this article is devoted to our first color: red.

Red Foods: Antioxidant Powerhouses

Red foods contain a high amount of antioxidant activity, thanks to phytonutrients called anthocyanins and carotenoids. First, we’ll get into anthocyanins.

Anthocyanins are water-soluble compounds with multiple aromatic rings and varying degrees of hydroxyl (-OH) groups. Often they are found in glycated forms, which means they are bound to sugar molecules such as glucose, arabinose, or rutinose. The aglycated form (meaning it is not bound to a sugar molecule) is called an anthocyanidin.

Anthocyanins have color because of their conjugated bonds, which means that their single and double bonds alternate. This characteristic gives them the ability to absorb certain wavelengths and also to delocalize and share electrons across its structure, an important feature for an antioxidant.

The most common anthocyanins have a familiar ring to them, as they are named after the flowers they are found in.

Common Anthocyanins in Flowers and Plants

- Cyanidin – red, reddish purple. Found in berries, red sweet potato, and purple corn.

- Delphinidin – blue, red, purple. Common pigment in blue flowers.

- Pelargonidin – red. Found in strawberries, cranberries, and raspberries.

- Peonidin – magenta. Found in berries, grapes, and red wine.

- Malvidin – purple, red. Common pigment in blue flowers. It is also the major pigment in red wine.

- Petunidin – dark red, purple. Found in black currants and is responsible for purple pigment of flowers.

You may be wondering how an anthocyanin, such as malvidin, contributes the blue pigment of flowers and also the dark red color of wine. That is because anthocyanins express their color differently according to pH. At acidic pH, such as in red wine, anthocyanins take on a more red tone. At neutral pH, they are typically purple and as the solution becomes more basic, they tend to be blue. Notice that red foods with high anthocyanin content, like strawberries, tomatoes, and red wine, are also quite acidic.

Nutritional Benefits of Anthocyanins

Like many other phytonutrients, anthocyanins are antioxidants. Their conjugated bond system allows them to donate an electron to neutralize free radicals, thanks to the ability of the molecule to distribute electrons evenly amongst itself to retain its own stability.

Furthermore, these molecules offer antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. These traits support overall systemic health and the relationship between anthocyanins and health, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, vision, and cognitive function, is well studied.

Anthocyanins aren’t the only components of red foods responsible for health benefits. Red fruits and vegetables also tend to be high in vitamin A, vitamin C, potassium, folate, fiber, and other flavonoids, such as pectin or quercetin. Spicy red peppers also contain capsaicin, another anti-inflammatory compound, though this nutrient is colorless.

Carotenoids are brightly colored nutrients that are present in red foods, such as tomatoes, watermelon, and papaya. Most carotenoids are orange and yellow and will be covered more extensively in the next blog of the series. Lycopene, the most potent antioxidant of the carotenoids, is responsible for the red color of these foods.

RECIPE >>> Cherry Gelato

Lycopene: An Antioxidant in the Carotenoid Family

Most carotenoids contain 40 carbons and fit into two categories, hydrocarbon carotenoids and xanthophylls. Lycopene is a hydrocarbon carotenoid, meaning it consists solely of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Like anthocyanins, lycopene contains conjugated double bonds, which contributes to its antioxidant activity and produces a vibrant red color. Many carotenoids can be converted to vitamin A, known as provitamin A, though lycopene is not one of them.

Like vitamin A, carotenoids, and hydrocarbons, for that matter, lycopene is fat-soluble. Thus, the bioavailability of lycopene is greatly enhanced when consumed with dietary fat. Fat-solubility is also the reason that tomato products stain plastic containers orange as lycopene sticks in porous surfaces. Cooking also greatly enhances the bioavailability and concentration of lycopene in tomato products due to water loss and heat disrupting the plant’s cells to release the nutrient.

Lycopene is a very well-studied nutrient, particularly in relation to cancer and cardiovascular disease, due to its well-known ability to reduce oxidative stress. Epidemiological studies show that higher intakes of lycopene are associated with reduced rates of cancer. In addition, lycopene may protect cells against the free-radical inducing effects of ionizing radiation and UV-induced damage (i.e. sunburn).

Tomatoes immediately come to mind when thinking about sources of lycopene, but other foods contain lycopene too. These include:

- Watermelon

- Pink grapefruit

- Guava

- Papaya

- Sweet peppers

- Red cabbage

- Asparagus (Yes, even though it’s green! Though not nearly as much as in tomatoes…)

Homemade Ketchup

Concentrated tomatoes, such as sun-dried tomatoes, pureed tomatoes, and tomato paste, have the highest concentration of lycopene. Ketchup and tomato-based sauces are the primary forms of lycopene in American diets.

Here is a homemade ketchup recipe that can be customized to your tastes and preferences.

Ingredients:

- 12 ounces tomato paste

- 2-4 tablespoons sweetener of choice (maple syrup, honey, agave, brown sugar, etc.)

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/8 teaspoon cayenne pepper

- ½ teaspoon garlic powder

- 1 teaspoon onion powder

- 4 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

- Water as necessary

Directions:

Combine all ingredients in a bowl, except water. Whisk together adding water in small increments to achieve desired consistency. Store in a glass jar in the refrigerator for up to a month.

Serve with roasted potatoes, eggs, burgers, or however you like your ketchup. Consume with healthy fats for maximum lycopene absorption.

Recipe adapted from Momables.

Next in the rainbow series: More carotenoids of the orange/yellow variety!

About the author: Karyn Lane is a current student of NTI’s Nutrition Therapist Master Program. She finds her chemistry degree a useful tool in her study of nutrition and loves to treat herself as a laboratory for new recipes and cooking techniques. You can follow her on Instagram @feel.alive.nourishment.

Learn more about our school by attending an Informational Webinar.

Images: Image by Viscious-Speed is free for use by Pixabay; Image by Steve11235 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0; Image by Engin_Akyurt is free for use by Pixabay; Image by kathas_fotos is free for use by Pixabay

Share this post!